Two years ago, a team of scientists published a research paper revealing the existence of what the scientists in the group termed an extraordinary bacterium. The organism used arsenic instead of phosphorus, and was therefore remarkable. Two new studies cast doubt on these discoveries.

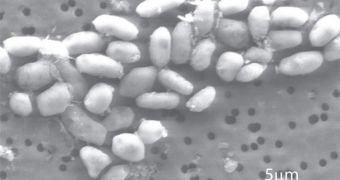

Back in 2010, following an extensive series of investigations conducted in the area around Mono Lake, in California, scientists from NASA found a bacterial species called GFAJ-1, which they said substitutes arsenic for phosphorus, in order to survive.

The announcement was received with a great deal of amazement, by both the international scientific community and the general public. Proposing the existence of a microorganism that can survive on a poison is indeed something worthy of admiration, and with significant implications for science.

But the enthusiasm was not long-lived. This Sunday, July 8, two studies were published in the top journal Science, refuting the claims made in 2010 by the NASA team. The papers argue that GFAJ-1 cannot and does not substitute arsenic for phosphorus, LiveScience reports.

“If true, such a finding would have important implications for our understanding of life's basic requirements since all known forms of life on Earth use six elements: oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur,” scientists in charge of editing the journal wrote yesterday.

Felisa Wolfe-Simon, who led the 2010 study, said at the time that the research sample she and her team were investigating did contain traces of phosphorus, but reasoned that these small amounts were not enough to support the growth of the extremophile bacteria.

The two new papers in turn suggest that this was indeed the case, and that the results of the 2010 study did not properly account for GFAJ-1's remarkable ability to scavenge even the smallest amounts of phosphorus from its environment, LiveScience reports.

It is precisely this capability that enables the bacteria to survive even if it has arsenic inside its cells.

As expected with such a daring study, the 2010 work immediately elicited rebuttals from other scientists, who argued that the methods used were prone to favor contamination and bias the results.

“The basics, growing the bacteria and purifying the DNA, had a lot of contamination problems,” explained University of British Columbia microbiologist Rosie Redfield this February. She was an author on one of the two Science papers published on Sunday.

Even with the publication of these two studies, the issue is most likely far from resolved, so keep an eye on this space for more information on this topic.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //