The bottom of the Southern Ocean is home to a type of circulation that moves very cold waters around Antarctica. Over the past few decades, this group of currents began disappearing at an increasingly faster pace, and scientists are currently puzzled over why that is happening.

A mass of water, called the Antarctic Bottom Water, is currently becoming warmer and saltier than usual, with potentially-significant implications for global heat transportation patterns. Oceanic currents, in general, play an important role in determining Earth's overall climate.

A few decades ago, this mass of water was significantly cooler and more widespread than it is today. A new research revealed the decaying trend, so researchers are currently trying to figure out how this shift influences temperatures and the climate.

Antarctic Bottom Water is usually formed at a series of locations around the Southern Continent. Cold air from above cools the water, which then goes on to accumulate the salt glaciers leave behind in unfrozen waters. The increased density then makes these waters sink.

Once they reach the ocean floor, they start spreading throughout all oceans, slowly mixing with warmer waters above. This exchange is critically important for Earth's heat and carbon cycles, experts say.

One of the first things researchers noticed was that this deep water was slowly becoming warmer and fresher, in tune with the evolution of glaciers on the surface. At the same time, new data indicate that lower amounts of such water were produced as a whole, LiveScience reports.

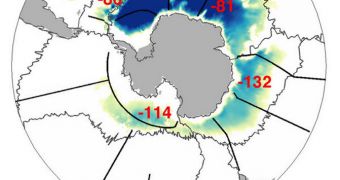

The data used for the latest investigation span three decades, from 1980 to 2011. The decline was estimated to exceed 8 million metric tons per second, which is about 50 times the average flow of the Mississippi River. The work was funded by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“In every oceanographic survey repeated around the Southern Ocean since about the 1980s, Antarctic Bottom Water has been shrinking at a similar mean rate, giving us confidence that this surprisingly large contraction is robust,” scientist Sarah Purkey explains.

She is a graduate student at the University of Washington in Seattle (UWS), and also the lead author of a research paper detailing the findings. Coauthors include NOAA Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory oceanographer Gregory C. Johnson.

“We are not sure if the rate of bottom-water reduction we have found is part of a long-term trend or a cycle. We need to continue to measure the full depth of the oceans, including these deep ocean waters, to assess the role and significance that these reported changes and others like them play in the Earth's climate,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //