A few decades back, cloning experiments belonged to the realm of science fiction, and few believed they would ever worm their way into reality. And yet they did.

1996 was the year Dolly the sheep, the world's first cloned animal, was born. Researchers have since cloned cows, mice, pigs, dogs and even a camel that, lo and behold, is now pregnant with its first calf.

Otherwise put, cloning experiments are becoming increasingly common. Hence, perhaps we should put our schedules on hold for just a while and try to figure out whether this is something to worry about.

First off, here's what cloning entails

The thing about cloning is that, although it's we humans that seem to have an oddly soft spot for it, it was nature that invented it way before we emerged as a species.

Plenty of bacteria, insects and even plants reproduce by cloning, meaning that they birth a brand new generation by creating genetically identical copies of themselves.

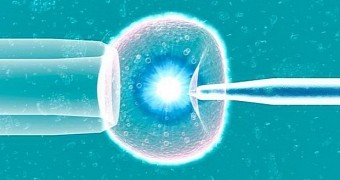

The form of cloning that some are worried about entails transplanting the genetic information contained within a cell into an unfertilized egg that no longer contains any genetic information of its own.

Rather than sit around waiting for genetic material from a father, as it normally would, the unfertilized egg uses the instructions transplanted into it to grow into an embryo and, eventually, an actual animal.

This is precisely how Dolly was born. Thus, to create this clone, researchers seeded an egg with the nucleus of a donor cell and then implanted it into a surrogate mother sheep.

To get the nucleus and the egg to fuse, they zapped them with electricity. It might sound easy-peasy, but it actually took a mind-boggling 276 attempts to engineer Dolly.

The perks of cloning experiments

As cool as creating copies of animals might sound, the fact of the matter is that there's more to cloning than just having genetically identical sheep, camels, pigs and whatnot running around.

Thus, scientists imagine using this technology to grow organs for people in need of a transplant. Since these organs would be grown from people's own cells, there would be no risk of rejection.

Cloning also has the potential to help infertile and same-sex couples have children who are genetically related to them, and would, technically speaking, allow parents to get back a lost child.

Besides, scientists believe that, by tampering with the copies they create, they might get a better insight into genetic diseases, maybe even figure out a way to cure them.

As for cloning animals and plants, this would make it possible to promote a set of very specific desired traits while at the same time phasing out the traits that are not to our liking.

Lastly, cloning would allow us to boost the overall headcount of plant and animal species that are now in danger of going extinct, maybe even resurrect lost species.

Mind you, it's not all fun and games

Strictly scientifically speaking, the chief problem with cloning is that one too many such experiments would translate into a loss of genetic diversity and, in turn, a higher risk of all sorts of diseases.

Besides, it's important to note that, in this day and age, cloning experiments end in failure way more often than they turn out to be a roaring success. As mentioned, it took 276 attempts to make Dolly.

Moreover, it can be argued that, just as cloning can serve to promote desired traits, the same technology can, in the wrong hands, be used to reproduce negative traits just for the fun of it.

As for using cloning to make human babies that are genetically identical to their parents or to a sibling, be they dead or alive, there are many who claim that such experiments would be unethical, to say the least.

This is because, rather than enjoy their uniqueness, as we all do, human clones would be viewed as somebody's copy and expected to behave just like the person whose cells were used to create them.

So, what's the bottom line?

True, cloning experiments can go horribly wrong. Then again, the same can be said about all other ongoing researcher projects, as well as about the cutting-edge investigations carried out in the past.

If we humans were in the habit of halting research work and experimenting every time there was a risk something bad might happen, we definitely wouldn't have made it this far.

So, the way I see things, cloning experiments should be allowed to continue, just as long as they are carried out in a carefully controlled framework and with very specific goals in mind.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //