Mankind has come a long way since its earliest days in the African savanna. As such, some of the emotions and heurisms that served us well over the eons, fear included, are no longer as relevant today as they were millennia ago. Scientists are now studying how to extinguish fear.

In many instances of our daily lives, fear has become more detrimental than useful. In the ancient wild, it helped our ancestors stay alive, but now it's causing a lot more harm to our daily lives than we would like to admit.

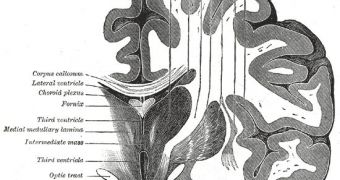

By studying the amygdala – the region of the brain past studies determined to be in charge of fear – researchers now hope to be able to understand the processes that lead to the formation and extinction of this powerful emotion.

Computer simulations now have enough data to start extrapolating on the phenomena that occur during this type of neural activity, say investigators at the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, in Germany.

ALUF expert Ioannis Vlachos, a PhD student at the Bernstein Center for Computational Neuroscience recently led a research team in developing a new explanation for why fears are generally only hidden, rather than extinguished entirely.

Details of the work appear in the latest issue of the esteemed, peer-reviewed journal PLoS Computational Biology, a publication of the Public Library of Science, PsychCentral reports.

One of the reasons why fears persist, the team says, is because their roots run deeper than the cerebral cortex, all the way to the amygdala. The fact that fears are generally “masked” in the human brain – that they run in the background, if you will – has been determined a long time ago.

In the recent study, it was determined that two major groups of neurons in the amygdala play a critical role in this process, so the team decided to simulate the activities of this neural network inside this region of the brain via computer models.

Results reveals that while one of the groups was indeed involved in fear response, the other acted in an exactly opposite manner, controlling fear suppression. It was also found that fear-suppressing neurons tend to inhibit fear-expressing ones.

However, though the former are rendered unable to send fear signals to the brain, the fear signals continue to linger within. As such, when the inhibitory neurons cease their activity, the fear signals reemerge to wreak their usual havoc in our thoughts.

These findings could lead to the development of new approaches for suppressing fear, which may for example include administering substances that support the functions of the inhibitory neurons.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //