The Amazon River is the largest on Earth, eleven times the volume of the Mississippi, and the second longest after the Nile, having a draining area about the size of the United States.

During the flood season, the river's mouth reaches 300 miles wide and up to 500 billion cubic feet per day (5,787,037 cubic feet/sec) flow into the Atlantic. The force of the current, from sheer water volume alone, causes the current to flow 125 miles inside the Atlantic before mixing with sea water. The Amazon basin is one of the centers of biodiversity on Earth, harboring 30% of the world's species.

Only the river itself possesses some 3000 species of fish (about half of the total freshwater fish species in the world).

Researchers have long suspected that the Amazon River once flowed westward, opposite to its current direction, from the Atlantic zone to the Pacific, maybe as part of a proto-Congo (Zaire) river system from the interior of present day Africa when the two continents were bound in the giant supercontinent Gondwana.

50 million years ago, the split South America collided with the Nazca plate from the Pacific, creating the Andes Mountains and blocking the flow of the Amazon. The river became a vast inland sea, which gradually plugged, becoming a massive swampy, freshwater lake.

Over 20 species of stingray living today in the Amazon are closely related to those found in the Pacific Ocean and not with those from Atlantic, proving that the river once had contact with the Pacific.

10 million years ago, waters broke the sandstone to the west, allowing the Amazon to flow eastward. During the Ice Age, sea levels decreased and the great Amazon Lake rapidly drained into the Atlantic becoming a river.

Recently, Dr Drew Coleman, a geology professor, and Russell Mapes, a graduate student at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, have incidentally found geological backing for all these theories. They were studying sedimentary rocks in the upper Amazon basin when he found ancient mineral grains in the center of South America which clearly originated in now-eroded mountains in the eastern South America.

If the Amazon had continuously flowed eastward, like it currently does, much younger mineral grains in the sediments, originating from the Andes, should be found. "We didn't see any," Mapes said. All along the basin, the ages of the mineral grains all pointed to very specific locations in central and eastern South America.

These sediments of eastern origin were transported from a highland area that formed in the Cretaceous Period, between 65 million and 145 million years ago, when the South American and African tectonic plates separated.

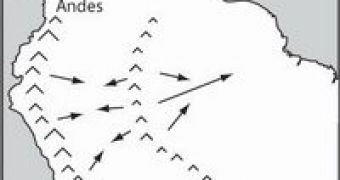

At that moment, a mountain bordered rift, like the present East African one, formed in the Eastern South America and Western Africa. Those mountains sent the river westward, carrying 2 billion years old sediments toward the center of the continent. A low height, the Purus Arch, still existing, rose in the middle of the continent, running north to south, dividing the Amazon's flow - eastward toward the Atlantic and westward toward the Andes. The Andes rising sent the river back toward the Purus Arch.

Sediment from the Andes, containing mineral grains younger than 500 million years old, filled in the basin between the Andes and the Purus, the river was blocked in the lake and after that forced eastward. The team collected zircon samples, a common mineral easy to date in order to see the age of the sediment's source, from about 80 % of the Amazon basin.

Previous studies identified the same reverse flow, but only in parts of the river. "The finding, Mapes said, helps illustrate that the surface of the earth is very transient. Although the Amazon seems permanent and unchanging it has actually gone through three different stages of drainage since the mid-Cretaceous, a short period of time geologically speaking."

Maps credit: University of North Carolina at Chapell Hill

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //