A group of researchers in the United States announces that it was finally able to develop an efficient method for reverting adult muscle cells to an earlier, stem cell state. This means that the newly-obtained cells can then be used to repair damaged tissue.

Thus far, this has only been demonstrated on unsuspecting lab mice, but experts at the University of California in Berkeley (UCB) say that there is no reason why this shouldn't work on humans as well. Mice are used as proxies precisely because of their similarities to us.

What is so interesting about the new achievement is that experts can take a piece of muscle, turn its mature cells into stem cells, and then co-ax the latter to develop into brand-new muscle tissue.

Details of the investigation appear in the September 23 issue of the esteemed scientific journal Chemistry & Biology. UCB assistant professor of bioengineering Irina Conboy was the principal investigator for this research.

This innovation “opens the door to the development of new treatments to combat the degeneration of muscle associated with muscular dystrophy or aging,” the scientist explains. She is also an investigator with the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3).

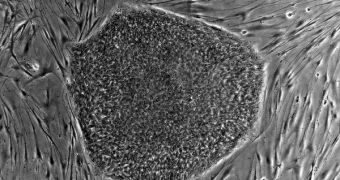

Conboy, a member of the Berkeley Stem Cell Center as well, explains that elongated bundles of fused myoblasts (individual muscle cells) form myofibers, what we refer to as muscular fibers. Muscle differentiation is considered to be complete when myoblasts fuse together into myofibers.

“Muscle formation has been seen as a one-way trip, going from stem cells to myoblasts to muscle fiber, but we were able to get a multi-nucleated muscle fiber to reverse course and separate into individual myoblasts,” the team leader explains.

“For many years now, people have wanted to do this, and we accomplished that by exposing the tissue to small molecule inhibitor chemicals rather than altering the cell’s genome,” she goes on to explain.

During the new investigation, the team determined that the reprogrammed stem cells they obtained did not cause tumors in the muscles of mice, even when they were injected in vivo. It's also worthy to note here that the cells the UCB team obtained are adult organ-specific stem cells.

What this means is that they cannot develop into other types of tissues than those in the organ from which they were harvested. In this case, the stem cells can only form new muscle tissue, and not much else.

“Rather than going back to a pluripotent stage, we focused on the progenitor cell stage, in which cells are already committed to forming skeletal muscle and can both divide and grow in culture. Progenitor cells also differentiate into muscle fibers in vitro and in vivo when injected into injured leg muscle,” explains Preeti Paliwal.

The expert, a post-doctoral researcher in bioengineering at UCB, was also the lead author of the new study. The investigation was sponsored by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (CIRM).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //