This is the agony of the medical world: finding a cure or a vaccine against HIV (human immunodeficiency virus). Now, the latest hit against the virus is an experimental drug that suppressed it to undetectable levels in people with highly drug-resistant strains.

The new chemical, TMC125 (etravirine), is the first of its type, after nearly a decade of research, in a class of three new drugs capable of stopping drug-resistant HIV and FDA could approve it this year.

"The new drugs offer the hope of treatment to perhaps thousands of HIV patients who have stopped responding to other medications," said co-author William Towner, medical director of the Kaiser Permanente HIV/AIDS research trials program. Maintaining the virus at bay could keep down the spread of drug-resistant varieties. The phase III of the trial tracked 591 subjects with infections resistant to the most common types of antiretrovirals (the common HIV medication). The subjects were given along with their preexisting regimens the recently approved drug TMC114 (darunivir) but also either TMC125 or a placebo.

After 24 weeks, the virus' presence was undetectable (under 50 copies per milliliter of blood) in 62 % of patients who received TMC125, while the number was 44 % in those receiving just the other drugs.

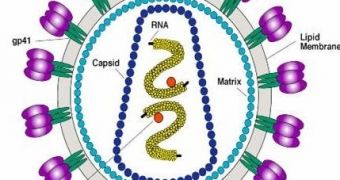

Antiretrovirals are assigned into three categories: nucleoside or nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors, depending on part of the virus they attack. Making cocktails from more than one class overcomes the quick mutating virus' ability to develop resistance and adding a single drug to a failing cocktail triggers virus resistance to it, too. And if a retroviral from one class has gone wrong, the whole class is compromised.

Just one mutation makes HIV insensitive to the three existing nonnucleoside transcriptase inhibitors. TMC125 attacks a part uncovered by antiretrovirals. In combination with darunivir and a third chemical, it decreased significantly the infection in 82 % of 82 subjects.

"This is the first example that a second generation of this class can actually be part of a new regimen," said HIV researcher Eric Daar of the Los Angeles Biomedical Research Center and the David Geffen School of Medicine at U.C.L.A.

"The development of protease inhibitors in the mid-1990s first made it possible to bring the virus to undetectable levels, but additional drugs trickled in one at a time. For many years we've had to make this hard choice when a cocktail fails. Do we add the one [new] drug and burn our bridges ? or do we wait for two drugs?" said Towner.

Two other new drugs, maraviroc and raltegravir, each the first in a new antiretroviral class, have been submitted for FDA approval.

"This is the second coming of HIV medical therapy. That's what makes [TMC]125 so exciting." said Towner.

"There is no recent tally of multidrug-resistant HIV but tens of thousands may harbor such infections." said Daar.

"In my clinical practice in Los Angeles, 15 to 20 % of his 300-plus HIV patients have a highly resistant virus. It hasn't exploded into a wildfire yet, but the potential exists. Doctors and patients will never apply medications perfectly, hence the existence of multidrug-resistant HIV. But with new cocktails on the horizon, the hope would be that in a sizable number of patients we could avoid any drug resistance." said Towner.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //