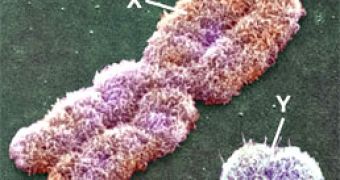

It seems simple: XX sex chromosomes make a female, XY sex chromosomes make a male. But sex is an evolutionary achievement which did not appear just like that.

A new research published in the journal "PLoS" points to the great similarities between the DNA sequences that determine the sex of plants and animals and the DNA that encodes the mating types in certain fungi (fungi do not have differentiated sexes, but mating types). Fungi investigation could explain the evolutionary development of sex chromosomes. Most plant and animal individuals have differentiated sexes: some produce tiny sex cells, called sperms (these ones are males) or a few large ones, eggs (in the case of females).

Fungi form the third eukaryote (DNA wrapped in a nucleus) kingdom, but they have the simpler system of mating types, characterized by variants of a few specific genes.

Sex in plants and animals has various determinations.

In humans, mammals, birds and insects, there are sex chromosomes. Fish and amphibians have sex genes. But the plant and animal sex differentiation must have emerged from the more primitive system of mating types, and this occurred several times independently of each other throughout the evolution of life.

The shift could have occurred with the inhibition of a stage in the DNA copying, which produced two separate chromosomes. These chromosomes evolved further over the geological eras.

"In humans (lineage), sex chromosomes are believed to have developed over the last 300 million years from a common 'proto-sex chromosome'," said lead researcher Hanna Johannesson of the Swedish Uppsala University.

The new research revealed that despite the lack of sexes in fungi, the genome portions responsible for sexual development in plants and animals and the DNA parts involved in determining the mating types in certain fungi are very similar. Such similarities were advanced in spore sac fungus (Neurospora tetrasperma).

"It's hard to study the evolution of sex chromosomes, partly because so many different and important sex-specific characters are tied to them. But much of this can be avoided if we use simpler systems, like fungi, as models," wrote the authors.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //