Since 1992, about 1100 objects have been spotted in the outer solar system, beyond Neptune's orbit. They are known as the Kuiper Belt. But at first astronomers have concentrated more on discovering these objects rather than tracking their orbits, so about half were never seen again. Then Minor Planet Center (MPC) at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics has started computing the preliminary orbits of these objects in order to try to observe them again.

However, as the MPC has only a few days' worth of data to work with, they cannot make very detailed calculations. They are forced to assume the objects follow common orbits that are either circular or linked to Neptune's orbit.

Nonetheless, although highly simplifying, these assumptions often proved to work, and the objects are seen again where expected. But the most interesting bodies are precisely those that don't follow such trajectories, because these are the ones that could tell us more about the formation of the Solar System. The bodies having regular orbits have in a certain sense lost their memory - exactly because their orbits are now regular one cannot infer much on how they were in the distant past. "It's those few unusual things that really tell you the story of the solar system," said Joel Parker from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

So, Parker together with Brett Gladman at the University of British Columbia, Canada, and others concerned themselves with the objects having important orbits that were escaping detection. They launched the Canada France Ecliptic Plane Survey in 2003.

This project consisted of repeated scans of the regions of the sky where distant objects are most likely to be found. After finding various slow-moving candidate objects, they tracked them for two years. In other words, instead of taking snapshots of a few days, they took short videoclips (at cosmic scale) of two years. "The study was to be as complete and free of 'recovery bias' as possible," Parker explains.

After two years they could finally give something to the MPC. The MPC computed the trajectories of these less regular Kuiper Belt bodies and produced estimations on where they are to be found now. 45 of them, range from about 50 to 500 kilometers wide, were just where they were supposed to be. This is a record announcement - the largest number of bodies with defined trajectories to be reported simultaneously. This has increased the number of distant objects with well defined orbits by nearly 10%.

The next step is to use this data for evaluating various theories about the formation of the Solar System. Different models make different predictions of how many objects should occupy certain orbits, so by measuring the distribution of objects over various types of orbits scientists can support or eliminate some hypotheses. This is what Gladman's group is now doing. They are analyzing the recorded data for determining how many objects have various orbits.

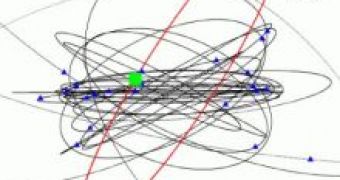

Image: the orbit of Buffy, an asteroid one-fifth to one half the size of Pluto, discovered by the Canada-France Ecliptic Plane Survey.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //