There never seems to be a consensus in regard to how much longer we have to wait for fully functional 3D printed organs, but Nanoengineers at the University of California might be able to have something ready in a few years.

That's not really what they've been trying to create though. Instead, they've been exploring other options, substitutes as it were.

More specifically, they used nanoparticles (tiny particles that are between 1 and 100 nanometers in size) to create an artificial organ that can neutralize pore-forming blood toxins.

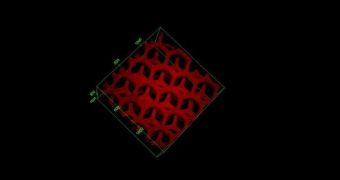

The team led by Nanoengineering Professor Shaochen Chen made a matrix that can be 3D printed from a hydrogel material. The matrix houses the nanoparticles which, in turn, do the whole toxin neutralizing thing.

It goes like this: the nanoparticles eliminate the substances that would, if left unchecked, spread through the bloodstream and cause anything from illness to death by poking holes through cell membranes.

There is a risk of secondary poisoning, sure enough, because the nanoparticles can enter the liver and accumulate over time.

However, with the hydrogel-based matrix, this is not a problem, especially if the thing stays outside the body. It's somewhat like having a dialysis device.

As for the bioprinting technique, it's called dynamic optical projection stereolithography and uses a liquid solution that contains cells and a photosensitive biopolymer.

The solution solidifies when bombarded with light, layer by layer. Essentially, the matrix is built layer by layer, or grown.

The method could be used for lots of other things besides substitute livers really, like human tissues, medical implants, treatment devices, etc.

“The concept of using 3D printing to encapsulate functional nanoparticles in a biocompatible hydrogel is novel,” said Chen. “This will inspire many new designs for detoxification techniques since 3D printing allows user-specific or site-specific manufacturing of highly functional products.”

The team from the University of California came up with their technology thanks to a $1.5 million / €1.09 million grant from the National Institute of Health. Between this breakthrough and others like 3D printed liver tissue, created from actual human cells, we could see fully 3D printed organs in a few years.

Compared to, say, the lungs and kidneys, the liver is relatively simple, despite being one of the most important parts of our bodies. Even if the prediction doesn't happen, out-of-the-body devices like Chen's liver-like matrix could replace or improve the effectiveness of some of today's most prevalent treatments.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //