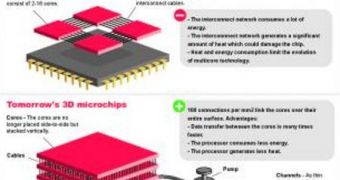

Not too long ago, home computers were powered by single-core processors, which needed to be continuously improved so as to get more power out of them. In time, dual- and quad-core designs emerged, which meant that two or four cores were placed alongside each other, sharing the tasks they were assigned. Now, experts are looking to create 3D computer processors, in which the cores will not be stacked next to each other, but on top of each other.

One of the main reasons why multi-core designs appeared in the first place was the fact that increased improvements in their predecessors meant that the temperature inside the computer rose as high as 85 degrees Celsius. This is enough to cause the electronics making up the microprocessors to malfunction, or exhibit peculiar, unexpected behaviors. The same problem will soon be met with the existing dual- or quad-core designs, and so experts believe that the solution at hand would be to use vertical stacking.

They argue that each core could be connected to the one below or on top via small connectors. It is estimated that a square millimeter of silicon chip could host anywhere between 100 to 100,000 connectors. This would naturally allow for a much higher transfer speed between the cores – up to 10 times faster than currently possible, by some estimates – as well as for improved heat efficiency and overall performance speed. But efficiency is not the only reason why 3d architectures are researched.

“In the United States, the industry's data centers already consume as much as 2 percent of available electricity. As consumption doubles over a five-year period, the supercomputers of 2100 would theoretically use up the whole of the US' electrical supply!” says John R. Thome, a scientist at the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne (EPFL), in Switzerland. The expert and his team are currently involved in studying a new, revolutionary cooling system that would further reduce temperatures inside future 3D microprocessors.

The work will most likely see practical applications around 2020. It is estimated that the first 3D processors will go into selected supercomputers around 2015, but without the cooling system. While large research facilities can afford to employ advanced methods of keeping temperatures in check, average consumers need to have the system already integrated into their machines. The EPFL, the ETH Zurich, and IBM are all contributing to this work, in which six research laboratories are involved.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //