English researchers at the University of Bristol publish a new study in this week's issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) showcasing how the fossilized tooth of a 30,000-year-old boy shapes our understanding of our species' evolution. The path that modern humans took in their adaptation to the environment is still shrouded in mystery in some places, mostly on account of the lack of fossilized remains that could confirm or infirm the various suppositions currently being made in the international scientific community.

The remains started being excavated about 11 years ago, from their site at Abrigo do Lagar Velho, in Portugal. UB Professor Joao Zilhao was the expert in charge of the extrication procedures, and his team managed to recover a set of remarkably complete remains. In anthropology and paleontology, the more complete the fossils, the richer the wealth of knowledge that can be obtained on their life styles, their gait, food, habitats, and so on. The child was classified at the time of the finding as being a modern human for all intents and purposes, but with Neanderthalian ancestry.

The discovery also ignited a heated debate in the international scientific community as to what exactly happened between early humans and the new variety, the Homo, when they met and started interacting for the first time, in Europe. This happened some 33,000 years ago, and some researchers hypothesize that the two distinct species of hominids interacted and cross-bred with each other, potentially producing offspring like the young boy the team discovered. The extent of these interactions has been a subject of dispute for a long time, and will most likely continue to do so until more fossils are found.

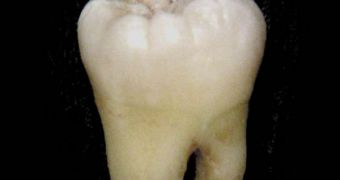

Commonly, experts say that the biology of early modern humans, which appeared in Africa some 50,000 years ago, hasn't changed much since. But not many specialists take into account the fact that late archaic humans, including Neanderthals, lived side-by-side with the modern humans in Europe for a few thousand years, before finally going extinct. So, an international team that also included Zilhao, decided to revisit the dentition of the Lagar Velho child, and compare it with both archaic and modern humans, including ourselves.

“This new analysis of the Lagar Velho child joins a growing body of information from other early modern human fossils found across Europe (in Mladec in the Czech Republic, Pestera cu Oase and Peştera Muierii in Romania, and Les Rois in France) that shows these 'early modern humans' were 'modern' without being 'fully modern.' Human anatomical evolution continued after they lived 30,000 to 40,000 years ago,” Zilhao says.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //