More than 1,500 years ago, a bustling social and economic center was located 50 miles (80.5 kilometers) south of Rome, the capital of the former Roman Empire. The settlement has only recently been discovered by British researchers at the University of Cambridge.

Experts say that no architectural features of the old town remain at its former location today. The area is covered over by farmlands (and the associated farms), and all remnants of the city are entirely buried.

The site, called Interamna Lirenas, is located in the Liri Valley of Southern Lazio, relatively close to Rome. The city itself is now believed to have been founded around the 4th century BCE, but did not reach its full spread and influence until about a millennium later.

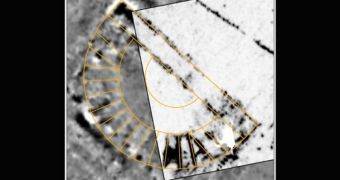

A mapping study of the location revealed the true spread of the city, which researchers say is quite impressive. For some reason, the entire location was abandoned some 1,500 years ago, for reasons still unclear, and the whole place was allowed to fall to ruins.

Scientists believe that scavengers then started to dismantle the settlement piece by piece, looting what could be looted, and then turning to the building materials themselves. Historically, cannibalizing the remnants of a city to build other structures is not uncommon.

Though no clear markings of the city remain, archaeologists managed to identify the location of some formerly important local buildings, including the theater and the marketplace. At the height of its days, the city covered a total of 25 hectares (250,000 square meters or 2,690,980 square feet).

Using a series of advanced geophysical research methods, the archeology team was able to determine the outlines of the former structures, and to map the way the buildings were spread throughout the city.

“Having the complete streetplan and being able to pick out individual details allows us to start zoning the settlement and examine how it worked and changed through time,” says Martin Millett.

Data show “that this was a lively and busy place, even though most scholars have reckoned that it was marginal and stagnating. We have also carried out research in the surrounding countryside which adds to the picture because it shows that the nearby farmland was thriving as well,” he adds.

The expert holds an appointment as the Laurence Professor of Classical Archeology at the University of Cambridge, and he is also a fellow of Fitzwilliam College.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //